Watch Astonishing Evidence of What Music Can Do for Alzheimer’s Patients

Henry, an advanced Alzheimer’s patient who barely speaks, literally comes to life in this video clip dramatically documenting how music can bring back memories and engagement. The clip is excerpted from “Alive Inside,” a documentary film that recently premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. It’s uplifting, touching and hopeful.

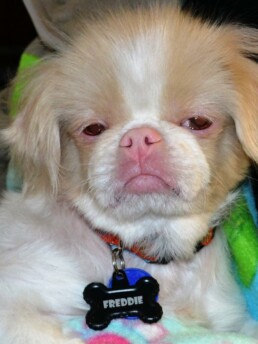

An Unshaggy Dog Story Unfolds at Ecumen Lakeview Commons

Fred had hit bottom. He was homeless and malnourished, living in a godforsaken shelter somewhere in Arkansas. His body was covered in sores, and his teeth were falling out. But even in this depth of despair, there was something about his spirit.

You could look through his eyes right into his beautiful soul. And that’s what saved his life. A stranger saw who he was on the inside and rescued him from certain death.

Now things are getting back to normal. Fred came to Minnesota and found a home with a woman who loves him dearly, and he is ready to give back to others who need support.

Today he went to visit a resident at Ecumen Lakeview Commons in Maplewood, Minn., who is in the last days of her life. He crawled up on the bed and let her know he was there for her.

Fred is an 11-pound, 8-year-old hairy albino Japanese Chin — a breed of dog cultivated by Japanese and Chinese nobility — specifically to live in the lap of luxury. He’s come a long way on his three-month journey from misery to bliss, and now has his own page on Facebook: [Furless Fred a Happy Tail].

Back in October, a rescuer from the Midwest Animal Rescue & Services had gone to a high-kill shelter in Arkansas to pick up a load of larger dogs and bring them back to Minnesota for adoption. As she was leaving, she saw Fred. He was wretched. He had mange, a yeast infection, a bacterial infection, an ear infection and bad teeth.

But that face… She just couldn’t leave him behind.

When Fred got to Minnesota, he settled into a foster home and was put up for adoption. The Facebook page was created to raise money for his considerable medical bills and to find him a home. He got plenty of attention, and people started donating doggie clothes to protect his ravaged body from the Minnesota cold. Fred, who by now was nicknamed “Furless Fred,” loved his new wardrobe and shamelessly mugged for the camera on his Facebook page.

Glory Hill, the housing manager at Ecumen Lakeview Commons, heard about him and went to take an in-person look. “When I first saw him, I fell in love with his face,” she recalls. At that point, he was a hairless, disease-ridden mess. But there was something about him.

That face. “I just couldn’t get him out of my mind,” Glory says. She didn’t adopt him on the spot. She wanted to think about it. And it was all she could think about until she went back and signed the papers.

Now Fred comes to work with Glory and has a good job at the Ecumen assisted living and memory care community. He’s totally off the meds, and his hair is growing back nicely— except on his tail.

Fred’s main job is to make people happy, and he is exceptionally good at it. He’s a champion snuggler. Residents often pop into Glory’s office and say things like: “If it’s OK, I’m going to watch Fred today while you’re at lunch.”

Fred’s main job is to make people happy, and he is exceptionally good at it. He’s a champion snuggler. Residents often pop into Glory’s office and say things like: “If it’s OK, I’m going to watch Fred today while you’re at lunch.”

Chins are bred to be easy-going companion dogs. Glory speculates that Fred was somebody’s very special dog before he fell on hard times. He definitely has companionship down. Only a truly evil person could walk away and leave him, so maybe he was stolen and then abandoned.

Whatever happened in the past, it’s surely behind him. Everybody is his friend, and nothing much upsets him. He enjoys going out in the lobby and sitting with all the folks who want to hold him. When Glory picks up his special blanket — the one he was wrapped in after his rescue — he knows it’s time to go to work.

But there is one little complication — another dog at Ecumen Lakeview Commons, named Bauer, who was here first.

Bauer, also a rescue dog, is a Border Collie-Australian Shepard mix, who belongs to Jen Rassmussen, the recreation therapy director. Bauer has his routine of walking around to visit his special friends. Maybe he’ll crawl in bed with someone and take a nap, or maybe he’ll chase a ball if somebody wants to throw it.

Bauer is a herding dog with lots of energy. Sometimes too much. Today he got kicked out of exercise class for being too rowdy. Whatever. He just went to memory care, where the recreational therapy group was falling asleep. Bauer lit up the room.

So Bauer and Fred are slowly checking each other out, literally circling each other when they are together. The staff is committed to making sure that both of these guys fit in.

They both have defined responsibilities, commensurate with their skills. Fred is an accomplished lap dog with superior cuddling ability, and Bauer is an expert on fun with an exceptional talent for frolicking.

It works: two rescue dogs, pleased to be working here at Ecumen Lakeview Commons, taking care of their people.

An Ecumen Consultant’s Quest To Make Sense of Dementia

Tom Stober, an expert on process and efficiency, was routinely going about his work one day when he walked into a room and came face-to-face with something that “shook me to the core.” It was not logical. It was not rational. The normal rules of organization did not apply. On some deep level, it rocked his orderly world.

It was a memory care community, where residents with dementia live.

Tom works for Minnesota Lean Partners, which had been hired by Ecumen over a year ago to improve customer experiences by teaching staff how to focus on what is truly important—what really adds value— and eliminating unnecessary things that get in the way of that goal. This was his first consulting assignment in senior services. A mechanical engineer by training, Tom had worked for many manufacturing companies, most notably Toyota, where he first learned the principles of “lean” management from the masters.

The Ecumen training sessions Tom was conducting were going well. He was teaching, and he was learning. But that first exposure to memory care was life-changing for him.

“I had heard about Alzheimer’s and dementia,” he says, “but I was never truly exposed to the impact that this has on the residents as well as their families.”

After visiting the memory care community at Ecumen Detroit Lakes, Tom remembers going to his hotel room that night preoccupied with his experience. He just could not get it out of his mind. “I was troubled by the degree that this bothered me. I struggled with the fact that these crippling diseases destroy what was once functioning human beings as mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers.”

There was just no apparent logic to it.

Yet as Tom watched the caregivers at work, he was in awe of “how loving, caring and forgiving” they were— and how effective.

“I was amazed at the strength and caring of the Ecumen staff working in this environment day-in and day-out,” Tom recalls. “Being briefly exposed to some of the behaviors that Ecumen care providers experience daily, it had a sincere and profound impact on me. I have a much higher appreciation for their contributions to the organization and their dedication to providing a high quality care to those that truly need it.”

A powerful emotion swept over him. “What I saw made me more dedicated to the work Ecumen is doing and made me want to help the staff more,” he recalls.

“I know caregiving is a job I could not do,” Tom says. “It takes a certain type of person.”

But he realized he is the certain type of person who could make caregivers’ jobs easier. That could be his way of coming to terms and making a contribution.

From Tom’s point of view, you can always make things better with organization, standardization and elimination of useless and wasteful practices—whether in a manufacturing plant or a memory care community.

“This could be my small way of paying it forward,” he decided.

On the most basic level, he noticed right away that caregivers spent a lot of time just looking for things they needed, often going in and out of rooms several times looking for supplies and equipment. So he helped staff systematically figure out how to put all the tools of care in the same place in every room. With everything they need easy to find, they are freed up to spend more time in direct care.

Then he started digging deeper. How can we organize care around the biorhythms of the residents? When is the best time of day to have activities? How can space best be used to optimize residents’ enjoyment? How can we improve the residents’ environment and create better experiences? Recently, he worked with the memory care staff at Ecumen Pathstone Living in Mankato, Minn., to completely revamp the memory care community. Go to Ecumen’s Changing Aging blog to read about this effort.

Over the past year and a half, Tom has trained more than 1,000 Ecumen employees in “lean” principles and has run more than 40 events to analyze situations and implement continuous improvements. And his work continues— not only in creating better practices but also sustaining them.

As Tom was working with Ecumen and coming to grips with his reaction to observing dementia firsthand, his personal story took another turn. Tom learned that his own father is now in the early stages of dementia.

The lean management expert bonded with the dementia experts at Ecumen.

“I have gained so much knowledge about dementia,” Tom says. “The Ecumen nurses have really helped me better understand what is happening with my father, and how it’s happening and the progression to expect moving forward.”

And the paying it forward continues.

—

Ecumen received a Performance-based Incentive Payment Program (PIPP) award from the Minnesota Department of Human Services beginning October 1, 2011 - September 30, 2015. LEAN the Ecumen Way is a company-wide initiative to improve the way Ecumen delivers services in day-to-day operations. LEAN focuses on eliminating non-value added activities in our work— “wastes,” which get in the way of the more important value-added activities that customers desire.

In addition to improving resident experiences by introducing LEAN management techniques, Ecumen has pledged to reduce antipsychotics among people with dementia and improve lives in all Ecumen nursing homes through its Awakenings program (see Ecumenawakenings.org). In 2010, Ecumen was awarded a three-year performance-based grant from the State of Minnesota’s Department of Human Services to expand its pilot Awakenings program to Ecumen’s 15 nursing homes. Such grants help organizations expand innovative, results-based initiatives. These homes serve more than 1,000 people, including some of society’s most challenging dementia cases. The Minneapolis Star Tribune recently profiled the Awakenings program.

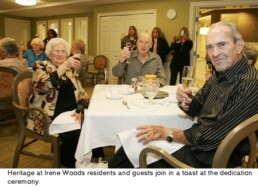

Heritage at Irene Woods in Memphis Hosts Official Dedication

Heritage at Irene Woods, a new Ecumen-managed senior living community near Memphis, Tenn., hosted its official dedication ceremony January 10, 2014, welcoming about 100 local officials, business owners and health care professionals for tours and lunch.

The dedication festivities included a program featuring Warren Rose, CEO of Edward Rose & Sons, the owner and developer of Heritage at Irene Woods and Julie Murray, Vice President of Sales, Marketing and New Business Development at Ecumen, along with local dignitaries.

Mark Luttrell, Mayor of Shelby County, sent a proclamation officially welcoming Heritage at Irene Woods to the community.

Heritage at Irene Woods recently opened with independent living, assisted living and memory care units. This is Ecumen’s first managed community in Tennessee and with partner Edward Rose & Sons, headquartered in Michigan. In the summer of 2014, Ecumen will begin managing another Edward Rose community in Clinton Township, Mich.

Heritage at Irene Woods provides 140 private apartments to people age 65+ all available on a monthly rental basis with no entrance fees. The community, totaling more than 165,000 square feet, has multiple common areas for the use of residents including three dining venues, a chapel, theater, pub, library, yoga/wellness center, salon and day spa, children’s area, Arboretum sun room, outdoor patios and garden areas. A team of licensed care staff are on-site 24-hours a day, for residents who need or require assistance.

The 150-acre Heritage campus, between Germantown and Collierville, will become a multi-generational neighborhood over the next five years that not only has a broad spectrum of senior living services, but also an adjacent multi-family apartment development sharing the amenities. The campus currently includes a three-story independent and assisted living building and a one-level memory care community with connected outdoor gardens and views overlooking Irene Woods.

For more information call 901-737-4735 or visit www.HeritageIreneWoods.com.

MacPhail and Ecumen Team Up For Dementia Music Therapy Program

The Minnesota State Arts board recently awarded MacPhail Center for Music in Minneapolis a grant of $96,690 to support music therapy for seniors with Alzheimer’s and related dementias, and Ecumen Centennial House in Apple Valley is one of the sites selected for the program.

MacPhail with be working with Ecumen and two other senior living companies, along with the Alzheimer’s Association of Minnesota-North Dakota, to provide music programs specifically designed for seniors with dementia-related memory loss. Work will begin in July to develop the therapy program at Ecumen Seasons at Apple Valley.

Studies have shown that music can reduce agitation and lessen behavioral issues common among those with dementia. Music helps people connect, even after verbal communication has become difficult.

According to the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America: “When used appropriately, music can shift mood, manage stress-induced agitation, stimulate positive interactions, facilitate cognitive function, and coordinate motor movements. This happens because rhythmic and other well-rehearsed responses require little to no cognitive or mental processing… A person’s ability to engage in music, particularly rhythm playing and singing, remains intact late into the disease process because, again, these activities do not mandate cognitive functioning for success.”

To read more about how music can help dementia, go to this Alzheimer’s.org explanation of how the therapy works.

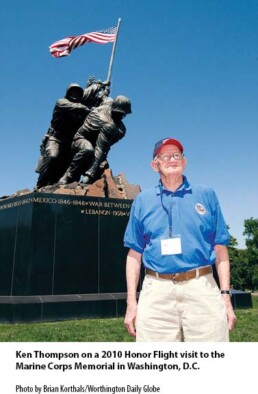

Ecumen Resident Ken Thompson’s Enduring Love Affair With Helen, Athletics and Worthington

The eyes sparkle and the smile widens as Ken Thompson’s thoughts drift back to the early 1940s. World War II is heating up after the attack on Pearl Harbor — and he will soon be going to Iwo Jima — but right now Ken is a star basketball player at Hamline University at a time when the Pipers are a powerhouse national championship team. And he is in a dance class at Hamline, where he is paired with Helen Backe, by happenstance of height.

The basketball coach had this idea that the team could improve coordination by dancing, so he brought in a girls physical education class to dance with the players. Ken (at 6-2) and Helen were matched as the two shortest in the class.

The basketball coach had this idea that the team could improve coordination by dancing, so he brought in a girls physical education class to dance with the players. Ken (at 6-2) and Helen were matched as the two shortest in the class.

They clicked, moving to the big band music. “We could really go up and down the floor,” Ken recalls. “But we had trouble going east and west.”

Quickly they figured it out. “By the sixth class, it was romance,” Ken recalls. “She was a honey.”

Now Ken is 93, and Helen died almost four years ago. At his assisted living apartment at Ecumen Meadows in Worthington, Minn., Ken enjoys reflecting on their 66 years together as they raised their family while he built a career as a legendary coach and athletic director at Worthington High School. Throughout all those years, they continued to go dancing every week. “It was just our special thing together,” Ken says.

This morning, before he starts telling his life story, Ken is doing what coaches do— replaying in his head last night’s basketball game that he watched between Worthington and Pipestone. He still cares about high school sports even though he has been retired from Worthington High School for more than 30 years. The measure of the man is that some of the athletes he coached still come to visit him at Ecumen Meadows. (They are now in their 70s.)

Ken grew up in Saint Paul, Minn., “as poor as grass” and went to Johnson High School where he was all-city in basketball in 1938 and also was an outstanding baseball player who later played semi-pro baseball in the Northern League.

But his dream was to play basketball for the renowned Hamline University basketball coach Joe Hutton. That would have to wait three years until he saved enough money to afford college by working at grocery stores and at Northwest Airlines. At age 21 in 1941, Ken became a freshman forward at Hamline and a star player for Coach Hutton.

At that time, the university was a national basketball power that produced a number of NBA players, notably Hall of Famer Vern Mikkelsen, who later became a teammate of Ken’s. “Since I had worked three years before I went to college, I was older than most players on the team,” Ken recalls. “Vern called me ‘Dad.’”

That 1941-42 season, the team won a National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) national championship. They were 23-1, losing only to the Harlem Globetrotters, who at that time played regular basketball. (In 1999 Ken was inducted into the Hamline University Athletic Hall of Fame.)

While he was at Hamline, World War II was raging, and in 1943 he enrolled in the Navy Reserve and reported to Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minn., as part of his midshipman school training. He was eligible to play basketball for the Gusties due to his military service and earned All-State honors that year. In 1944 Ken went on active duty in the Navy and was stationed on the USS Missoula, which was carrying Marines to the Pacific islands. In June of that year he took a brief leave to marry Helen.

While he was at Hamline, World War II was raging, and in 1943 he enrolled in the Navy Reserve and reported to Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minn., as part of his midshipman school training. He was eligible to play basketball for the Gusties due to his military service and earned All-State honors that year. In 1944 Ken went on active duty in the Navy and was stationed on the USS Missoula, which was carrying Marines to the Pacific islands. In June of that year he took a brief leave to marry Helen.

Ken commanded landing crafts from the Missoula that took the Marines on shore at Iwo Jima. He proudly remembers watching the dozen Marines hoist the flag from his ship on Mount Suribachi in what would become probably the most famous photo from World War II.

Shortly afterward, he helped land troops on Okinawa, where the Japanese kamikaze pilots were “flying so low I thought they were going to take the top of our heads off.”

The war ended while he was still aboard the Missoula, and he remembers sailing past the USS Missouri the day the final peace agreement was signed in a surrender ceremony on that ship—Sept. 2, 1945. That was a very good day, but on so many other days he saw “so many men lose their lives.” Ken’s gaze drifts back those 70 years and clearly the memories are still painful. He clouds over and changes the subject.

With the war done, Ken returned to Hamline and played two more seasons of basketball, qualifying for another national tournament but losing in the third round. In one memorable game against DePaul University, Vern Mikkelsen fouled out, and Ken, at 6-2, was tapped to guard the 6-10 DePaul University star George Mikan, who, like Mikkelsen, went on to play in the NBA for the Minneapolis Lakers.

In 1947, Ken and Helen moved to Worthington. His first year there, he coached at the junior college, then moved to Worthington High School as head basketball coach in 1948. In his first season as coach, he led the Trojans to their first District 8 championship since 1926. The team would go on to win two more district titles in 1951 and 1952 during his 11-year stint as basketball coach.

“I used to say that basketball was a class I taught, and the test was every Friday night.”

During this same period, he also coached baseball, football and golf and taught earth sciences at the high school and middle school. He was a self-proclaimed “rock hound,” who spent several summers in programs that advanced his training as a geologist.

Ken says he was not a coach who yelled and screamed because “I didn’t have to.” He remembers the kids who played for him, almost without exception, as being hardworking and dedicated. In his whole time as a coach, he cut only one player.

In 1959, he became the athletic director at Worthington High School, a job he held for 24 years, while continuing to coach golf. His 1957 golf team won a state championship, and in the 28 years he coached golf his teams won 22 district championships in a row and nine regionals. As athletic director, in addition to supervising and mentoring the other coaches and handling the budgeting and administration of sports programs, he ran the district basketball tournaments.

In 1982, he retired after 36 years with District 518. For a while after that, he managed the Prairie View Golf Course in Worthington. Two heart bypass operations slowed him down, but up until last May when he moved into Ecumen Meadows, he lived in the family home in Worthington, which he still owns.

Over all these years, Ken and Helen raised two daughters, danced and played golf together, and made Ken’s sports career a family affair. Helen would go to the basketball games with the kids and her ever-present scorebook in tow. She intently scored all the games—“always by the book.” Like Ken, she too would be named to the Worthington Trojans Hall of Fame for her dedication as a Trojan athletics booster.

Ken looks back on those days thankful for how blessed he was. The job was great, the kids who played for him were wonderful, and his family was supportive.

“I never walked into that school a day wishing I didn’t have to,” Ken says.

AgePower Tech Search Announces Five Finalists

Five finailsts have been named for the AgePower Tech Search, a collaboration between Ecumen and MOJO Minnesota.

Ecumen Pathstone Living Adds State-of-the-Art Treadmill To Its Rehabilitation Equipment

Ecumen Pathstone Living in Mankato, Minn., has added a LiteGait® Treadmill to its transitional care center allowing older adults to more safely begin rehabilitation walking programs after injuries, surgeries and hospital stays.

The treadmill’s suspension technology reduces the risk of falling, allowing older adults in rehabilitation programs to resume walking with more confidence.

“Thanks to the help from several generous donors, we can now offer this state-of-the art equipment as part of our rehabilitation program,” said Beth Colway, Ecumen Pathstone Living’s development coordinator. “This new treadmill opens up additional options for our physical therapists to help older adults recover from injuries or surgeries and return to living in their homes.”

Beth said the new treadmill cost just over $20,000 — fully paid for by donations.

With some older adults, regaining the ability to walk after hip fractures or other lower body injuries can be extremely difficult. Some never regain the ability to walk because they can’t endure the necessary physical therapy that incorporates walking and weight bearing activities. By utilizing LiteGait®, Pathstone therapists can offer programs that safely increase the possibility of walking again.

LiteGait® explains the capabilities of its treadmill this way: “Our patented system maintains the patient in a secure, upright position. By reducing the risk of falling, LiteGait provides a safer therapy environment. More than just and extra pair of hands, LiteGait’s most important effect is the confidence it inspires in patients. In a process that is often difficult and painful for both patient and therapist, LiteGait® encourages a sense of accomplishment, progress, and ultimately, success.”

LiteGait® can assist with numerous types of therapy, including postural support for sitting, standing, walking and running, pain-free movement that encourages walking with normal gait mechanics, partial weight bearing, upper body mobility, balance and coordination, neurological gait training, geriatric conditioning, fall prevention and weight control programs.

In the photo, Grace Carlson, a resident of Ecumen Pathstone Living Short Stay Care Center, is assisted on the new LiteGait® treadmill by Becca Gish, a physical therapist.

—

Ecumen Pathstone Living, which has been serving the Mankato area for more than 75 years, provides services including skilled nursing care, short-term rehabilitation, memory care, and assisted living apartments. Pathstone also offers home care, adult day services, and catering services. More than 500 people each day benefit directly from Pathstone services. Ecumen Pathstone Living is owned by Ecumen, the most innovative leader in senior services. In 2004, Ecumen Pathstone Living opened its transitional care center providing short-term therapy and rehabilitation, which now serves approximately 350 adults each year.

SVP Steve Ordahl Tells the Star Tribune How Ecumen Got Ahead of Change in Senior Housing

The Star Tribune recently interviewed Steve Ordahl, senior vice president of business development at Ecumen, about his insights into how senior housing development has changed in the past decade, and what he sees ahead for the marketplace.

Steve retires January 15, 2014, after guiding Ecumen’s development and diversification efforts for the past 10 years and helping make the company a leader in creating new options for seniors.

Director of Nursing Maria Stokka To Retire After 35 Years at Ecumen’s Pelican Valley Health Center

For the past 35 years, Maria Stokka has been coming to work as the director of nursing at Ecumen-managed Pelican Valley Health Center, providing care to the families of Pelican Rapids. On February 28, 2014, she will retire from this job that has intricately connected her with the lives of the 2,500 people who make this northwestern Minnesota community home.

“When you have done a job like this for 35 years, you’ve taken care of more than one generation,” Maria says. “You get to know families and extended families at some of the most important times in their lives. They are your neighbors — and sometimes your relatives.”

In fact, Maria’s mother was in the care center here, and her husband’s mother and father both were here.

When Maria, originally from Fairmount, N.D., graduated from St. Luke’s School of Nursing in Fargo, she didn’t envision a career in long-term care nursing. She and her husband moved to Pelican Rapids and there was a job open at another care center, where she worked for five years until her first child was born. After that, she started working nights at Pelican Valley Health Center and was quickly promoted to director of nursing.

“Once I was in it, I had no desire to do any other type of nursing,” she says. “This is so much more personal. You know the residents. You know their families. And you’re there for them at some of the most important times in their lives.”

Barbara Garrity, the Executive Director at Pelican Valley Health Care, says working with Maria “has been an absolute honor.”

“She is so easy to work with and always does her job with the residents’ well-being in mind,” Barbara says. “She is also an exceptional, hands-on leader, and the staff has the utmost respect for her.”

The respect is mutual. Maria describes her management style as a team approach. “It takes the whole team to get the job done right,” she says. “No one job is more important than another, and everyone has something to offer. I respect and appreciate what others do. And I remind them that what they do is really important.”

And that outlook has led to some incredible employment histories for the nursing department. Several other nursing department staff members, including Maria’s sister, have more than 30 years of service at Pelican Valley. “The longevity of the staff here can be largely attributed to Maria’s leadership,” Barbara says.

Maria says she strives to always be open, honest and fair. “I don’t sugar coat. I don’t overreact. I talk things through and encourage others to do the same.”

So why retire now? “I want to leave while I’m on top of my game,” Maria says.

She plans to spend time traveling with her husband, Jerome, who is now retired. They have a son and a daughter in the area and four grandchildren, who she will now be spending more time with.

In her spare time, Maria does crafts like beadwork and embroidery and also likes crosswords and reading.

Will she miss the job she has been doing for the past 35 years? “Oh, I’m sure there will be a big void,” Maria says. “But I’m not leaving the community. I’ll still be seeing everybody.”